The Chicago regional branch of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) is housed in a white building that looks like something between a set of circus tents and a vision of the future from the 1960s, which at this point looks extremely dated. But the warehouse that actually holds the documents it keeps looks pretty much like any other warehouse: big and rectangular, except that this one is next to a small military outpost, with rows of camouflaged jeeps nearby.

I decided to pay a visit shortly after Thanksgiving because the court records from the 1992 criminal case from the Gary, Indiana drug ring led by Lee Andrew Edwards resided in four boxes in that warehouse. That case went to appeal more than once at the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, after which the records were returned to the district court in the Northern District of Indiana. Decades later, they were sent to the NARA warehouse in Chicago, Illinois.

The Indiana criminal court case didn’t name Bola Tinubu as a defendant, and it didn’t even mention him once in the papers so far as I could tell. But it resulted from the same FBI investigation that later swept up Tinubu and his Nigerian co-conspirators, and there was a lot of useful context that I thought might appear in the documents, none of which were available on-line from the court. The only way to obtain them was to go to Chicago, make an appointment with NARA, reserve the one overhead Fujitsu ScanSnap scanner—designed to never need to touch the original pages—and start scanning.

Four boxes may not sound like a lot, but with each box holding about 2,500 pages, it’s a considerable amount of paper. A day of scanning might yield 500 pages, so it would take about three weeks to scan every page in each box. My hope was just to scan the pages that were most important.

The first box happened to contain one of the most interesting sets of documents: the transcript of the trial in Indiana, which had to be compiled and entered into the record for the Seventh Circuit appeals. Once I finished scanning the transcript, which did mention Abiodun Agbele and his link to Nigerian heroin a number of times, I also came across a set of documents I had not expected to be filed in court: records from the FBI investigation itself.

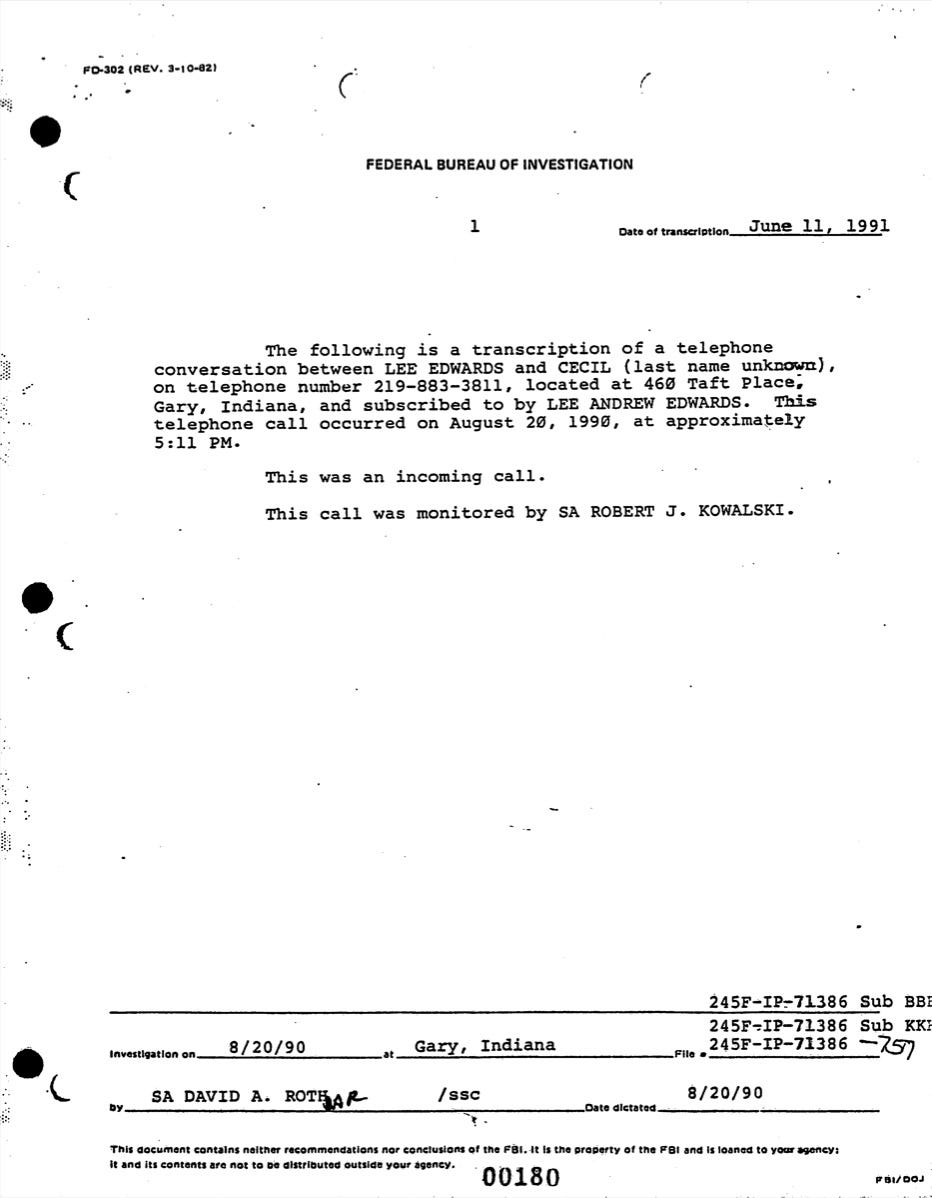

The prosecutors had decided to enter as evidence transcripts of the telephone calls that the FBI had monitored thanks to the numerous Title III wiretaps they had obtained. The calls mostly concerned transactions for drugs, but the records were remarkable for a different reason: there were no redactions. While FOIA documents are often redacted, sometimes to the point of absurdity, these documents were not being produced via FOIA. They were simply sitting in a box from the court case.

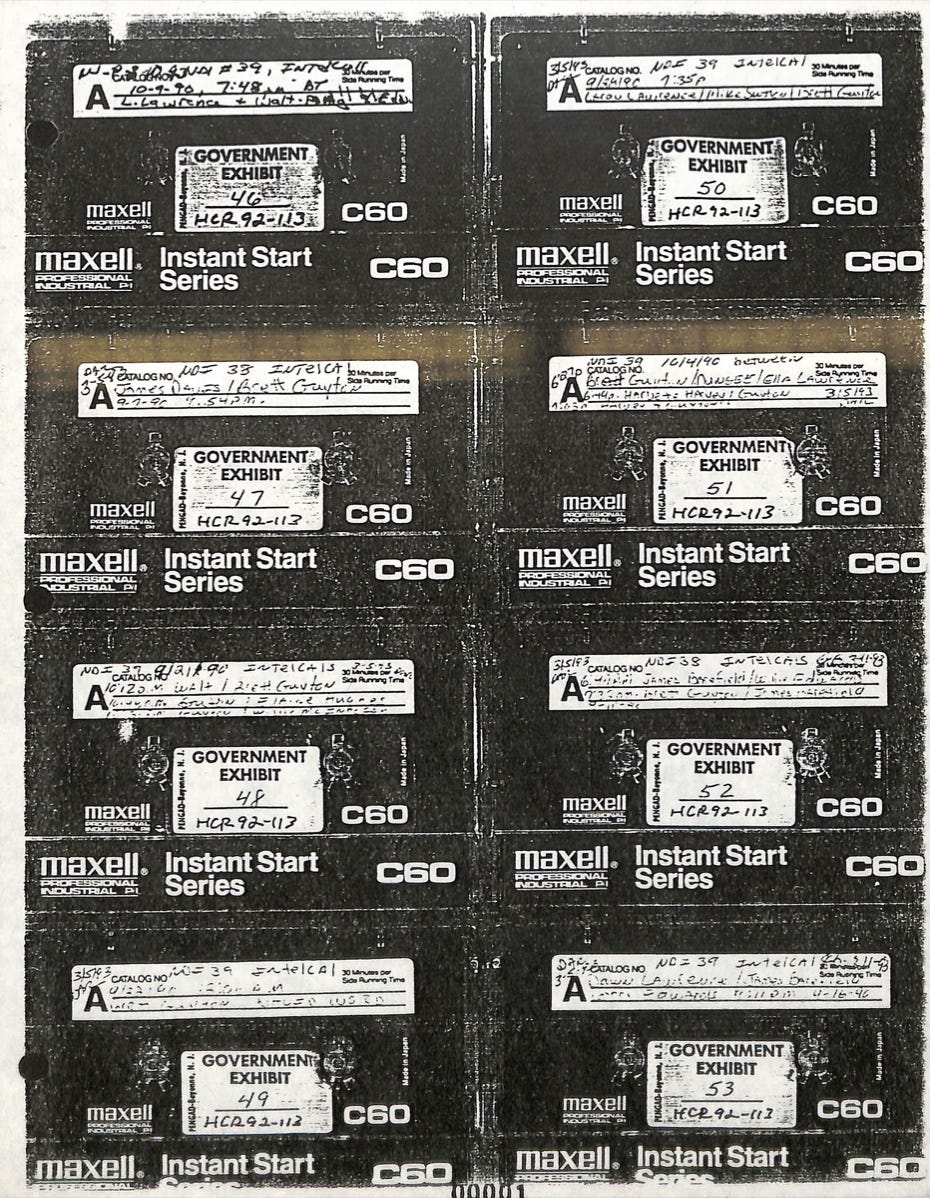

The FBI recorded the Edwards narcotrafficking ring’s telephone conversations on cassette tape, and submitted transcripts of the recordings as evidence in court.

The information at the bottom of each FBI Form FD-302 was a puzzle piece I didn’t even realize I had been looking for. Each form had a “File #” field in which the FBI had recorded not just the main file number, but also the sub-file numbers for what appeared to be each individual connected to that recording: an early version of tagging. It seemed that sub-file numbers began at “A” and continued as long as there were people to categorize, starting over at “AA” and then “AAA” and so on. This was interesting because the tipster who provided the FBI file number to request about Bola Tinubu had specified FBI file number IP-71386-UUUUUU, in what seemed like a joke at the time. Now, it appeared that “UUUUUU” was Bola Tinubu’s specific sub-file in the sprawling file for the overall FBI investigation, which spanned multiple continents.

A sample FD-302 from the court documents stored at the Chicago National Archives, without redactions.

The metadata at the bottom of each page also noted the names of the Special Agents assigned to each recording, which were being redacted through the FOIA process. The fact that these were already publicly disclosed in the 1990s—if you could find them—meant that there might be a chance of removing those FOIA redactions as well.

This made me wonder about a name I had encountered in the trial transcript: Special Agent Karen Pertuso. When I went back through the files to find her testimony, however, her name seemed to have changed: I was looking at testimony from Agent Robert Pertuso, instead. After some further research, I realized that there were actually two Agent Pertusos on the case: they were a married couple. Much later in their careers, according to the Washington Post, this practice of both of them working together on the same case landed the FBI and each of them in hot water, and they retired from the FBI.

I also managed to scan a few interesting procedural documents from the court case. One noted the history of how the case was prosecuted, and seemed to leave open the possibility that it was not the only court case to come out of the FBI’s investigation, but rather, the only one we could see. ECF No. 602, filed March 29, 1994, stated that “On July 2, 1992, the U.S. Attorney’s Office received from the FBI a prosecutive report regarding the Lee Edwards drug trafficking organization. The report was 6,469 pages in length.” Yet the FBI had indicated previously that it found only 2,500 responsive pages. What happened to the other 4,000?

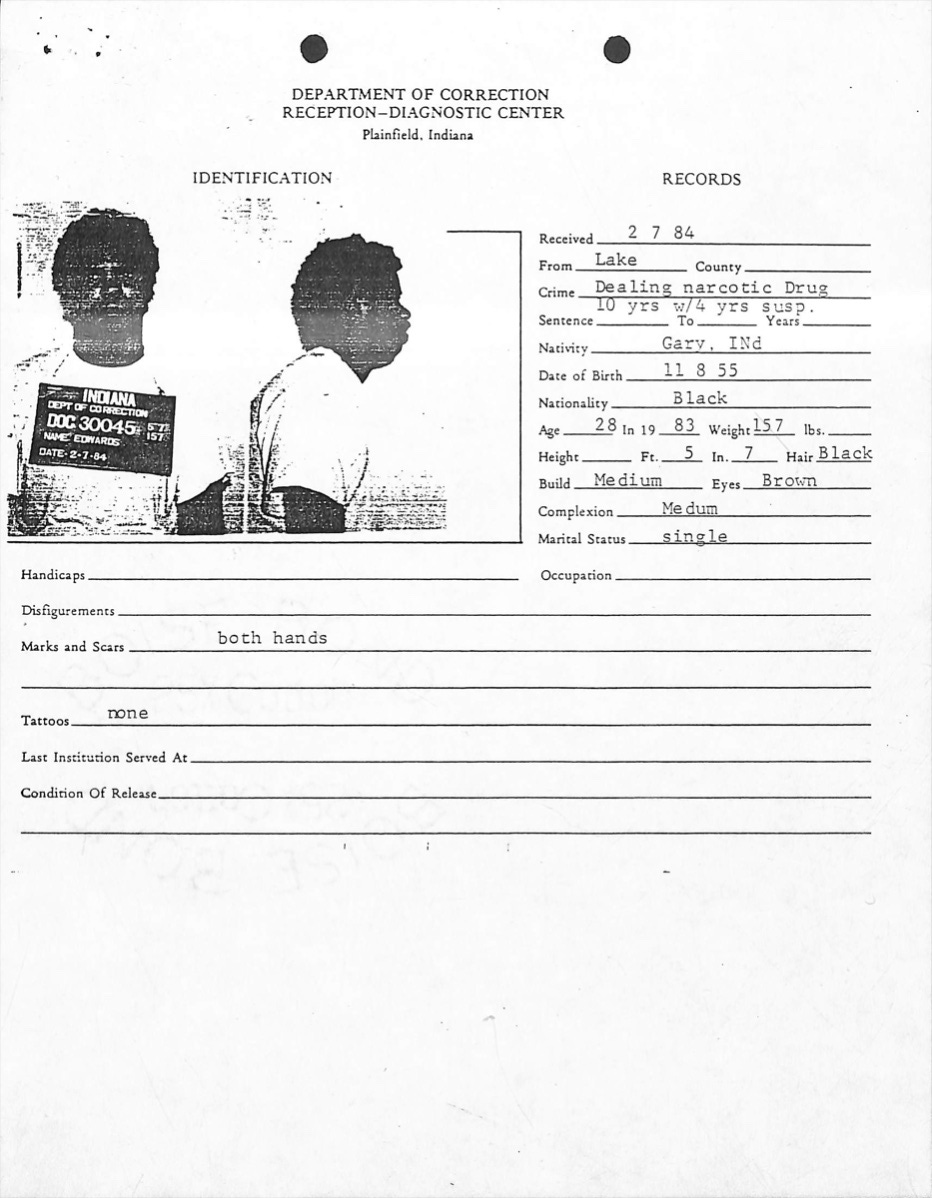

There was even a photocopied photograph of Edwards from a prior conviction in Indiana, also for selling drugs.

Lee Andrew Edwards, whose funds derived from selling heroin on the streets of Chicago, Bola Tinubu, now Nigeria’s President, laundered.

The visit to the National Archives had turned up more clues than I expected, but there was one last stop I wanted to make. I headed to the federal building in downtown Chicago, which houses the United States Court for the Northern District of Illinois. There, on a public terminal, I was finally able to see the original scans of the court documents from Bola Tinubu’s civil forfeiture case—not the grainy, fake-looking scans that had been posted by Sahara Reporters. After handing over $28.00 at $0.50 per page, I finally cajoled the court clerk to e-mail me copies of the original PDF files from PACER, which are not available through PACER anywhere else on Earth due to a March 2011 Judicial Conference policy that restricts the availability of scanned documents from archives, on account of the fact that they may contain Social Security numbers. It was hard to argue against the policy; Tinubu’s case materials contained several, though they were ironically probably stolen to start with. Eventually, I received the files from the court via e-mail, and replaced the grainy images on PlainSite.

I had obtained pretty much everything I had been hoping for from my Chicago trip. Now, all that was left to do was convince the United States Department of Justice that it was provable that records naming Bola Tinubu in the context of the FBI and DEA investigations into his money laundering actually existed.

To be continued in Part IV…